n 2020, it’s been harder than ever to have a truly good night’s sleep. With the world in disarray as a pandemic threatens our safety and wellbeing, I know that I am not alone in seeing a heavy uptick in nightmares, including dreams about death, disease, and general distress. Superliminal is about dreams and dream-logic, and represents a sort of nightmare itself, but it’s a different kind from the ones I’ve experienced. For all its confusing geometry, strange logic, and growing unease, it’s ultimately an optimistic and satisfying experience. Superliminal offers a short, enjoyable run through a subconscious in crisis, and it’s a consistently clever and pleasantly challenging game with a lot on its virtual mind.

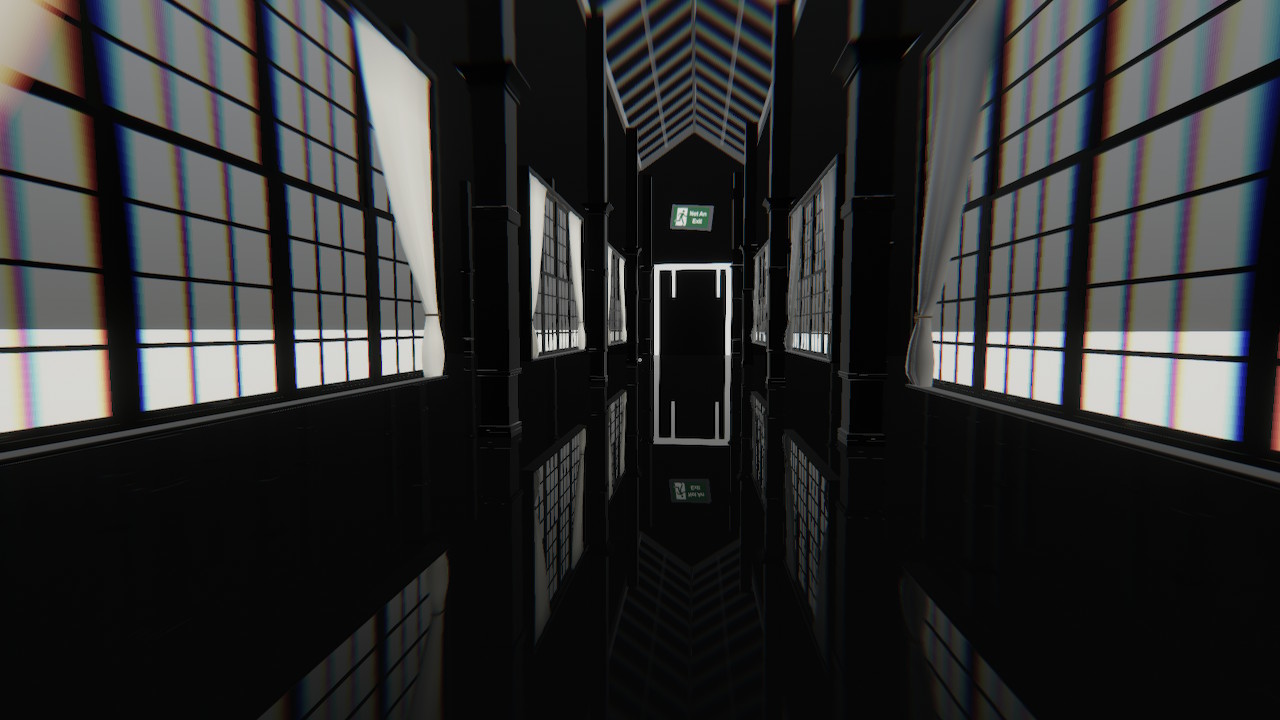

You play as a patient of Dr. Glenn Pierce, one who is undergoing the Somnasculpta sleep therapy program. The whole game is set within your medically induced dream as the program probes your subconscious, asking you to complete a series of challenges to find peace of mind and overcome feelings of inadequacy and self-doubt. Things go wrong fast, though; you take a wrong turn and stumble deeper into a dream state than was intended, and the deeper you go, the further your surroundings shift from a recognizable reality. It’s like Portal’s puzzle chambers crossed with the dream spaces of Inception (and a hint of Alice in Wonderland too), but despite those clear influences Superliminal feels like its own thing.

To get through the game, you’re told to view things from a different perspective–although it might be more accurate to say that the game is about taking your existing perspectives and reconceptualizing them. The puzzles in Superliminal all revolve around your first-person viewpoint, and you have to figure out what elements of each environment you can manipulate. A lot of this involves resizing objects through an extremely satisfying mechanic–if you hold up a small square block in a hallway and position the reticule so that the block looks like it’s far in the distance, you can drop it… and it’ll now be much larger and located down at the other end of the hall. Similarly, if you grab something large in the distance and then look straight down, you can drop what is now a tiny object on the ground in front of you.

It’s like Portal’s puzzle chambers crossed with the dream spaces of Inception (and a hint of Alice in Wonderland too), but despite those clear influences Superliminal feels like its own thing.

It’s a cool trick, and it’s one Superliminal goes back to often. In fact, a few too many of the puzzles in Superliminal involve holding small objects above your head so they look far away, and then dropping them several times as they grow successively larger. But despite some repetition, the game is far from a one-trick pony, and even just in the way things grow and shrink there’s some variety. To explain the game’s best puzzles too specifically would be to ruin the joy of discovering their solutions, but there were moments where I plucked objects unexpectedly out of the background, or discovered secrets hidden inside small objects after enlarging them, or the camera tricked me into believing in an object that wasn’t there.

Throughout the game, I found objects that would spawn infinitely as I tried to interact with them, or which would only appear if I looked at a room from a certain angle. I enjoyed mazes with abstract solutions and delighted at some clever uses of recursion that would be difficult to properly explain in words. The game’s bag of tricks is impressive, and even if ideas do repeat, you can expect surprises throughout. Superliminal is big on illusions, from forced perspective tricks that make 2D paintings look 3D to misleading distant sights that look very different up-close to non-Euclidian environments and impossible spaces. You’re often made to reconsider your relationship with the first-person camera, how objects appear within the screen space, and whether you’re relying too much on real-world logic to solve puzzles.

Notably, you don’t possess a body in the game–mirrors reflect nothing, and you have no hands or legs to speak of. While in other games this might make you feel distractingly disconnected from your environments, that disconnect is at the heart of Superliminal–you have to re-learn how you exist within each space. It looks fantastic on Switch and performs well even in instances where a room is full of objects that can be manipulated. The art style shifts as you move through the game, with environments ranging from clinical white-and-orange chambers to the more fantastical settings you encounter at the end–all of which look great.

There’s also a simple narrative pull as you fall deeper and deeper into your dream state. There are thin slices of narration planted throughout the game from Dr. Pierce and an AI assistant, but the game’s environments also beautifully communicate the danger your mind is in as they grow more abstract, and as you find yourself in areas that are seemingly not meant to be part of your therapy. The story ends up being a little on-the-nose, as you might expect from a game where looking at things from a different perspective is the primary play mechanic, but it’s ultimately effective at making you feel like the light workout you gave your brain in reaching the credits was good for you.

I finished Superliminal in about two and a half hours, and while the game’s deliberate pacing means that I wouldn’t want it to be too much longer, there are still some sections that feel truncated, a few ideas that don’t feel fully explored. The game is divided into nine chapters, each dealing with slightly different ideas and aesthetics, and some of them wrap up incredibly quickly. This means that some ideas feel underused, and it’s difficult not to wish that some of the mechanics were taken further. It speaks to how much I enjoyed Superliminal that I was disappointed when it ended so soon, though. I wanted to see the game’s fantastic conceptual framework stretched to its limits.

Superliminal is a great puzzle experience, full of smart ideas that are richly realized. The game’s playful use of the first-person camera and clever perspective manipulation puzzles take video game tropes and mechanics most players will be familiar with and wring something truly fresh out of them. Superliminal achieves its clear central aim–it offers up some genuinely fresh perspectives on what first-person puzzle games can do.

More Stories

Doom Eternal review

Review: The Last of Us Part II complicates the idea of right and wrong

Dirt 5 review