What is it? A moderately interactive adventure about androids developing their own consciousness.

Expect to pay $40/£30

Developer: Quantic Dream

Publisher In-house

Reviewed on Core i5-8400, GTX 1060, 16 GB RAM

Multiplayer?No

Link Official site

Best known as the centre of the U.S. car industry and the birthplace of Motown, the titular city of Detroit: Become Human has fallen on hard times. But the virtual Detroit of 2038 has found a second life as heart of the android industry. This has left the populace unemployed all the same, causing them to regularly mistreat their artificial servants. It’s this constant injustice that eventually causes androids to develop their own consciousness.

You follow the story of three such androids—Connor, a brand-new investigation unit developed to help the police with casework involving his errant brethren; Kara, a household model who rescues a young girl from her abusive father; and Markus, another artificial butler who is falsely accused of harming his owner.

You take control of each in turn, following them through a chapter before switching to the next protagonist. If you’ve played Heavy Rain or Beyond: Two Souls, you know what to expect: a mixture of interacting with items using Quantic Dream’s cumbersome control scheme and mashing buttons during quicktime events. This way, action sequences such as chases are less thrilling and more anxiety-inducing thanks to the potential of pressing the wrong button and messing the whole thing up. And yet this is still a marked improvement over Beyond: Two souls, most of which you spent as a poltergeist toppling items.

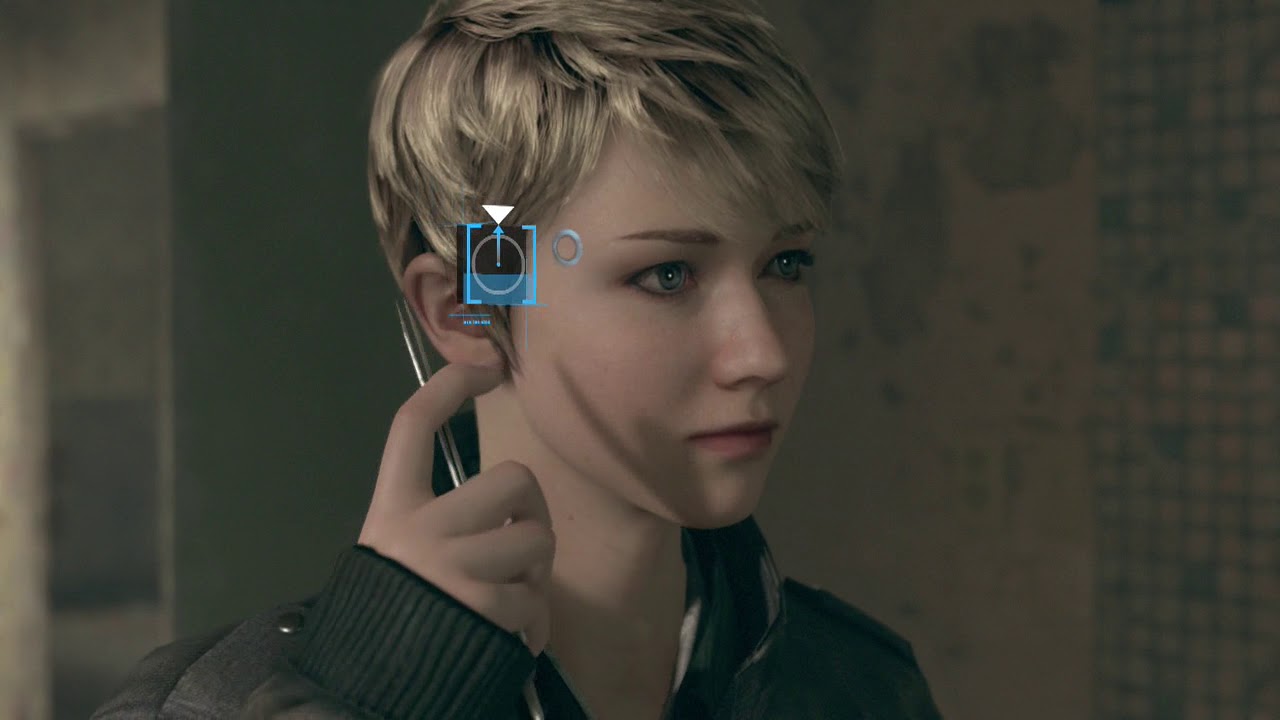

While the keyboard controls are much more coherent than those of Beyond: Two Souls, where no limb would ever respond to just one button, I still can’t endorse them and recommend using a gamepad. Visually, Detroit is an absolute stunner, but unlike Heavy Rain and Beyond: Two Souls—the PC versions of which look markedly better than even their PS4 remasters—Detroit comes out looking much the same, with a 30 fps cap (note: while I couldn’t free it from a 30 fps cap, some say they got a 60 fps cap working) and no difference between low and ultra settings. Even the Windows 98-style mouse cursor spells hasty PC port, but it runs without issue.

The most important aspect of Detroit is without a doubt its story, ambitiously setting up a full-scale android revolution—your three characters in the thick of it—and a myriad of branching storylines depending on your actions. It’s the longest game by Quantic Dream so far, and the most intricate, to the point that after each completed chapter, you see a chart with each possible path. From a narrative design perspective, it’s impressive stuff. You get to experience both dramatic choices with immediate impact as well as twists that don’t occur until much later. All of this leads to a large number of both good and bad endings. That’s not to say every choice makes sense. Some choices you make contradict previously established motivations, but the point seems to be that they exist nonetheless, and that you get to make certain decisions yourself.

Bluescreened

However, Detroit is still a game written by David Cage, as incapable of subtlety as ever. Whether its equating the uprising of previously non-sentient beings with North America’s enduring interracial struggle—to the point where androids travel in the back of the bus and later quote Martin Luther King Jr.—or continuing to include female characters in his stories only to see them victimised, I have never seen work so in need of a sensitivity reader. Overall better than the previous games, the quality of Detroit fluctuates depending on whose plotline you’re playing. The story of Connor, who is partnered with surly veteran Anderson, brings some much needed levity, making good use of the buddy cop trope.

In fairness, much of the writing is better than Quantic Dream’s previous games. Gone are the days of Heavy Rain’s “we can do this the easy way or the hard way”. And with mo-cap this good, the actor’s are given ample opportunity to let their facial expressions do the talking rather than the game spelling everything out.

Much of Detroit: Become Human doesn’t work because there’s no emotional payoff for the horrors you witness.

There’s also some good detective play, in which you find clues until Connor can put the M.O. together in his artificial mind’s eye. By comparison, Markus gets to lead a revolution simply because he’s there and turns out to be the most charismatic among a thoroughly unlikable band of bots, and Kara’s main function is to be a vehicle for the glorifying of violence against women. Each of the three main characters can die if you’re not careful, but Kara’s death leaves no dent on the plot, nor does she develop as a character.

As a person of colour and a woman, I simply don’t see the necessity of strapping a conscious female character onto a torture device, or likening black people to machines through allegory. You have to be aware how it reads to people of certain demographics when, during your shader compilation, players are shown a screen on which every android servant is a person of colour, and the romance model is Caucasian. Honest mistake or not, these associations are exactly what racial conflict is about, and instead of reflecting that, Detroit perpetuates age-old stereotypes.

Sure, it’s a good-looking game that offers parts much better than the overall sum, but I do believe that much of Detroit: Become Human doesn’t work because there’s no context; no emotional payoff for the horrors you witness. Why include child abuse in a game if no character is ever going to mention it again? Why does this specific character feels suited to lead a revolution? Why does no one question him? Everything that happens in Detroit, save for Connor’s plot, feels disconnected, a chain of escalating events for maximum effect.

What you end up with is a game with very high production values, of which only one third is ever truly enjoyable.

Read our review policy

Occasionally fun but often unconscientious, Detroit: Become Human takes steps in the right direction but retains too much of the old Quantic Dream formula.

More Stories

Doom Eternal review

Review: The Last of Us Part II complicates the idea of right and wrong

Dirt 5 review